All bears but one taken by my sons, son-in-law and I were hit in the heart. One, I shot with a rifle in the neck at a range of 15 feet, shattering its spinal cord; it dropped in its tracks.

Several bears I have inspected, shot by other hunters, were hit in the brain. They all dropped in their tracks. Their skulls, unfortunately, were gruesomely shattered.

One bear I inspected had been shot in the neck by a bow hunter. It took three days of very skilled tracking to recover this bear.

Twice I have been asked to aid in tracking leg-shot bears. One bear was tracked 12 hours; the other, three days. Sign eventually petered out and neither could be recovered.

Another I heard of was hit in a ham (no bone involvement). After bathing itself in the shallows of a lake some distance from where it was shot, its trail completely disappeared.

Two other bears that I was asked to help recover were shot in the abdomen, one through the stomach (stomach contents identified on the bear's trail) and the other farther back (feces leaking from its wound). Neither of these fatally shot bears were found during two days of tracking.

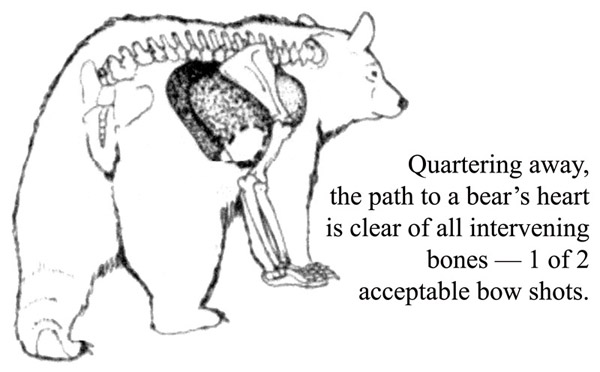

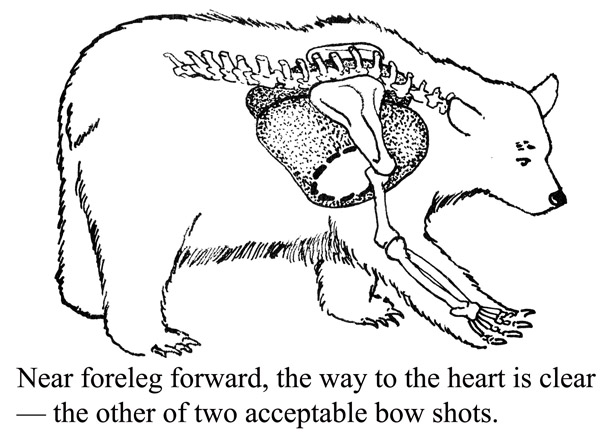

Shot from steep shot angles by bow hunters last fall, two bears I know of were hit in scapulas (shoulder bones) and another in the spine. All ran off and none were ever seen again. Some bears, perhaps all, that are hit in the scapula with an arrow recover. The bear I took in 1989 had fully healed after being hit in the scapula a year or more earlier, the broad head remained embedded in the bone.

By the time several hunters I talked to found their fatally crippled quarries, the bears had completely spoiled. Not even the hides could be saved.

Sad tales of crippled and lost bears are legion among hunters who fail to hit a black bear's quick-kill, heart/lung region. If such tales do not end, once and for all, bear hunting will surely end, once and for all.

It will happen fast: one second, there will be an unsuspecting black bear feeding complacently before you and the next second it will be gone. Unlike its approach, however, the fatally-hit, panic-stricken bear's departure will be reckless and noisy. Initially, the bear will plunge forward in whatever direction it was facing when hit, unmindful at first of brush, trees and windfalls in its path. A fatally-wounded bear will make a lot of noise as it flees. When it can run no farther (vital tissues depleted of blood and oxygen), it will fall to the ground, likely groan or roar three to five times, and then quickly die.

Throughout your quarry's last desperate flight, you must keep your wits about you. It is extremely important that you follow its progress with your ears and eyes, taking note of specific landmarks along its path. When no more sounds are heard and/or no more glimpses of the fleeing bear or movements of the cover it pushes through are seen, take note a distinctive landmark (a certain tree, for example) at the spot where you last heard the bear, saw the bear or saw moving cover, dig out your compass and get an exact bearing on it. In the extreme excitement of the moment, it can be easy to forget all sorts of things, but do not forget this. If your bullet or arrow did not make a low exit wound, thus failing to make an easy-to-see trail of blood, this compass bearing and that single landmark may be your only means of locating your fatally shot bear.

Now, finally, go ahead and be human. Rejoice. Allow yourself to act like a hunter who has just succeeded in doing something quite remarkable in the annals of big game hunting. Sit back in your stand, grin, stretch, take some deep breaths and relax.

If you feel suddenly drained at this moment, your arms and legs very heavy, clumsy and shaking uncontrollably, that too is "normal" under such circumstances. You are merely suffering the aftermath of having your body charged with enormous levels of adrenaline and blood sugar. There is nothing like bear hunting for doing this to a hunter. It will probably take about ten minutes before you will feel physically normal again; able to climb to the ground without hurting yourself, in command of your body and senses. You should remain seated in your stand for at least ten minutes in any rate. This is no time to rush off in pursuit of a bear. Let nature take its course first, in you and in the bear.

If you know you hit your bear in the heart/lung region, and you actually heard its death groans, there is no need to hurry. The bear is not going anywhere. Depending somewhat on the bear's size, it is probably lying dead not far from your stand, most likely within 40 yards.

Whatever you believe or know at this moment, however, never allow yourself to be absolutely certain your shot was quickly fatal. Hope it was, but from this point on, never believe a bear is dead until the bear is down, silent, motionless, not breathing and does not blink when an eye is touched with the tip of a long stick. Until then, it is far wiser and far safer to accept the possibility that the bear is not only still alive, but it will still be alive when you find it.

A shot that is not quickly fatal being a distinct possibility, you must allow the fleeing bear time to lie down as soon as possible, within the shortest possible distance from your stand. When hit, the bear probably had no idea what happened. It probably did not connect its injury with a feared human. Even upon hearing a thunderous shot, it probably thought it was injured by another bear. If not pursued by a human soon after its initial flight, it will probably lie down within 200 yards of your bait site. If not disturbed there, blood loss and shock will eventually take their toll, likely rooting the bear to the spot or weakening it enough to make it easy to approach and finish. If human pursuit is evident very soon after being injured, the bear will become fueled by adrenaline and blood sugar, after which it will travel much longer and much farther before lying down again, and it will be much more difficult to kill. A fully-aroused, wounded black bear can withstand enormous physical injury before dying. Worse, when approached by a hunter, a fully aroused, wounded black bear might also become dangerous. Unless the bear went down within sight of your stand, it groaned or roared three to five times, you can see it and is not moving, never begin trailing a shot black bear until ten minutes have passed. Also, though it is extremely unlikely the bear will be dangerous under any circumstances, never take to the trail of a hit bear, especially one that did not groan or roar three to five times, until your wits are restored and without being prepared to defend yourself.

How long should you wait after the shot before taking to the trail of a bear you are not certain is dead? At least one hour. Use this hour to return to camp to rid of unneeded hunting gear, to pick up a lantern and a heavy-duty flashlight, to enlist the aid of one or two bear tracking partners and to alert your dragging crew.

Some good rules for safe and effective tracking of a wounded bear are as follows:

Rule 1: If you are not certain your shot was quickly fatal, do not trail or approach an unseen, potentially-live black bear alone. This is a tow-man job, commencing no less than one hour after the shot, one person keying on trail signs and the other keying on the area ahead and to either side, poised to fire, if necessary, when the bear is sighted.

This is not an entire, anxious-to-see-the-bear, dragging crew job. The larger the tracking group, the less likely it is that you will succeed in drawing near enough to a wounded bear to be able to make an effective finishing shot. Admonish others in your group to wait patiently in camp or wait silently at your bait/stand site until help is requested or until some pre-arranged signal is given, three gunshots, for example; whereupon the draggers are instructed to follow the trail of toilet tissue squares impaled by you on branches along the bear's escape route.

If a finishing shot is needed, aim for the bear's heart/lung region, not its head or neck.

Rule 2: While trailing a wounded black bear, move slowly and silently. Do not talk out loud. Do not even whisper. Communicate via hand signals or pencil and paper only. Stop often and listen. Do not proceed into any area that has not been visually scanned first. By day, use binoculars to scan. Even in very dense cover, binoculars are very effective for spotting downed or crippled black bears while yet a safe distance away.

Rule 3: From beginning (bait site) to end (location of dead bear), generously mark the path taken by the bear. Squares of bathroom tissue impaled on high branches make wonderful trail markers. They are easy to spot from a distance, non-damaging to trees and biodegradable. Not only will trail markers aid in relocating a "lost trail" when sign is scant, but once the bear is found, the marked trail will probably be the surest and shortest route back to your cleared stand trail, the path you will want to use when transporting your bear from the woods.

If you do not have an easy-to-see blood trail to follow, be sure to mark the significant landmark(s) you noted from your stand as the bear fled. If you can not positively identify these landmarks from the ground, return to your stand platform and direct two partners, one watching you, the other for your bear, to these landmarks via silent hand signals. With your compass in hand, direct your partners (as they lay a tissue trail from your stand) to the exact spot where you last saw and/or heard the bear. Once these landmarks are pinpointed and marked, you can join your partner(s) to begin a more intensive search for signs and/or the shot bear.

Whether the length of the trail to your bear is 25 yards, 165 yards or longer, your most obvious tracking sign will be blood. If hit properly (your bullet or arrow passing through the heart and lungs and making a low exit wound) profuse, external bleeding will begin within one to ten yards of where the bear was hit. A spray of fine droplets of blood may be found beyond the spot where the bear stood when hit, but unlike a fleeing heart/lung-shot white-tailed deer, exuding fine sprays of brightly colored blood widely to either side of its trail each time its hoofs hit the ground, the trail of a rapidly fleeing, heart/lung shot black bear will typically be marked by a series of large drops and elongated dollops of brightly colored blood, usually about every one to three yards. The reason is, a black bear's dense under-fur is like cotton. It absorbs considerable blood as it flows from the wound and causes blood to flow downward along a bear's body rather than spray outward. Wherever the fleeing bear paused or slowed down (nearing death), larger puddles of blood will be found. Drops and broad smears of blood will also become common on foliage, branches and tree trunks brushed by the fleeing bear, mostly on the side of the exit wound. If lung-shot, the quantity of blood will gradually increase and remain steady. Such a blood trail will usually lead quickly to a very dead bear.

Keep in mind a black bear can run 30+ mph, meaning, theoretically at least, one could cover 293+ yards in 20 seconds. I have never personally known a heart or lung-shot black bear to travel farther than 165 yards. Most drop within 40 yards.

If your bullet or arrow passed through heart and lungs but did not make an exit wound, little or no blood sign is likely to be found until very near the place where the bear went down. It takes considerable hemorrhaging inside before significant blood can fill the chest cavity to the height of the entry wound and make its way through the underlying fat and fur. By the time significant bleeding begins, the bear may already be dead.

A trail that begins with profuse bleeding but wanes (spots of blood becoming fewer, smaller and/or farther apart) means the bear was not hit in the heart/lung region.

If the bear was not immediately pursued and laid down within 100-200 yards, its bed identified via flattened vegetation and pooled blood, it was seriously wounded; probably fatally wounded.

Note the height of blood smears along the bear's escape trail and keep in mind a wounded bear will lie down facing its back trail. This information plus the position of blood evident within or about the bear's bed (oblong area of flattened vegetation) will help to determine the location (part of body) of the bear's wound(s).

If hit anywhere within its abdominal cavity (from the rib cage back), the bear will certainly die; probably within six hours if liver or kidneys were damaged; more slowly (perhaps taking one to three days or longer) if its stomach, intestines and/or urinary bladder were damaged.

If the blood trail begins quickly enough, bleeding profuse at first, but then blood gradually ebbs, perhaps abating completely within 100-300 yards and the bear not lying down within that distance, it is likely the bear was hit in a leg or ham, a non-vital part of its neck or a superficial part of its torso. Considerable skill and determination will be required to recover the bear.

Scattered black bear hairs at the shot site reveal the bear was hit, but they cannot reveal how seriously. Long black hairs probably mean it was hit in the torso somewhere; short, wiry black hairs, in a lower limb. When trailing a bear that otherwise provides no evidence of being injured, black hairs found clinging to branches along a bear's escape route do not necessarily mean the bear was hit by your bullet or arrow.

White hairs at the shot site indicate the bullet or arrow pierced the bear's brisket. White blazes are not uncommon high on the centers of chests of black bears. If shot with an arrow while quartering away, white hairs generally mean the heart was missed but the near lung was damaged and maybe major blood vessels that course into a bear's neck, a wound which may or may not be quickly fatal. If white hairs are found after a shot was taken head-on, using a high-powered rifle caliber such as a 175-grain, 7mm Magnum (a shot angle to be avoided when using a bow), the trail to the bear will likely be very short, the heart and/or large blood vessels at the top of the heart almost assuredly damaged. It takes plenty of foot-pounds of energy, however, to penetrate deeply enough into a black bear from this angle. With lesser calibers, lung damage is certain, but not necessarily with quickly fatal effect.

Very short tan hairs at the shot site indicate the bear was hit in the muzzle. A bear hit in the muzzle that does not immediately fall to the ground will be very difficult to recover, and if not recovered, it may live a considerable time before dying from its wound or starvation, being unable to consume foods.

Bone fragments may be found at the shot site or along the bear's escape route. Rib bone fragments, relatively thin with flat surfaces, usually mean the wound will be quickly fatal (a heart/lung or lung hit). Bone fragments that are thick and rounded usually mean the bear was hit in a limb or lower shoulder. If hit in the lower shoulder by a bullet while the bear was standing broadside, the wound will probably be quickly fatal. If the bone of the lower shoulder is shattered by an arrow, the bear may travel several days before succumbing.

Bloody, undigested or partially digested bits of foods previously eaten by the bear mean the bear was hit in the stomach. Bloody feces (droppings) and/or urine mean it was hit far back in the abdomen. Though there are major blood vessels in the abdomen that when hit can result in massive, quickly fatal bleeding (descending aorta and ascending vena cava), stomach or intestinal contents along the bear's escape route generally mean the hunter has a long and arduous task on his or her hands.

When hit in heart and/or lungs, a black bear will flee with little regard for obstacles in its path. Though not always obvious, foliage and branches along its escape route will be bent in the direction taken by the bear and ripped, trampled and/or broken. If an established deer trail is handy, a wounded bear will likely use it, in which case damage to vegetation and branches will not be evident.

Paw prints of the fleeing bear will be evident where the ground is wet or soft. The bear's trail will also be distinguishable in deep grasses, grass pressed flat where paws hit the ground and bent in the direction taken by the bear. Where fallen leaves cover the ground, freshly-turned and ragged hand-sized bunches of leaves, notably darker on their newly exposed undersides, mark the bear's escape trail.

When on the bloodless trail of a wounded bear (no exit wound), it is especially important to mark the locations of less obvious signs made by the fleeing bear. Indistinct signs soon lose their appearance of "freshness" and human passage can easily destroy them. Each indistinct sign by itself may only be suggestive of a fleeing bear, but when each is marked, many of such marks (of tissue paper) will line up to form an obvious trail.

A wounded black bear that travels more than 200 yards without lying down was obviously not hit in the heart. For that matter, it was probably not hit in a lung either, meaning, it will be a tough bear to recover.

Whatever the nature of a bear's wound, it is a hunter's obligation to make every attempt to secure a speedy and humane end to the suffering of a wounded black bear. Not only is it ethically and morally wrong to shirk such a duty, but if you do, you may even indirectly endanger the life of an innocent human, someone who accidently stumbles upon your wounded bear. Upon making the decision to hunt black bears, accept the fact that you might find it necessary to spend an extra day or two afield in order to properly finish a bear.

Under the best of circumstances, a wounded bear's trail is easily lost. After the shot, the bear may travel a considerable distance before external bleeding begins. It may flee through impregnable cover, water and/or over treacherous terrain where detours are necessary. The bear may pause to lick its wound, causing the blood trail to suddenly disappear. Loose fat beneath the bear's hide may temporarily plug the wound. The bear may double back on its trail and then turn off at an unexpected place. Falling rain may wash away sign in unprotected areas. Darkness may add to the burden. There are lots of reasons for temporarily losing the trail.

When it becomes obvious the trail is lost, return to the last identified sign, its location marked by a square of white tissue paper impaled on a high overhanging branch. Using the line of tissue papers behind you as a guide, move five yards to one side, circle through a 180-degree arc (half-circle) ahead, searching carefully for signs as you go, until on the opposite side of the end of the trail. If noting is found, move out another five yards and trace another half-circle, continuing in this manner through ever widening arcs until the bear's trail is once again discovered. This usually works.

If upon searching through 10-20 of such arcs, 50-100 yards from the end of the trail, the bear's escape route has not yet been discovered, suspect one of three possibilities: 1) the bear quit bleeding, 2) it turned sharply away or back from its previous line of flight, or 3) it is lying dead where not easily spotted near the end of the trail. Mortally wounded black bears not uncommonly make a J-like movement to the left or right shortly before death. Go back, then, to the last sign and begin making ever widening, "full circles" out to 100 yards about this point until the bear or its trail is discovered.

No bear sign within 100 yards? No blood, no tracks, no freshly broken branches or no flattened vegetation? Now what? Do it again, only this time occasionally mark your progress with squares of tissue paper to make sure you do not miss an area greater than five yards in width. If you still fail to find a trail or a dead bear, extend your search out to 200 yards. If a search of this magnitude does not turn up something, assume the bear was not as seriously wounded as you thought, it quit bleeding and abandoned the area with great haste.

Trailing a bruin in the dark is not an uncommon necessity in black bear hunting. There are two reasons: 1) black bears are often shot shortly before sunset and 2) dead black bears (not field dressed) spoil very quickly. The trouble is, it is illegal to carry a firearm or bow in the woods after sunset. Unless I am absolutely certain I have fatally hit a bear (I definitely shot it through the heart and/or lungs), I would not attempt the eerie task of trailing and approaching a medium-to-large, wounded black bear in the dark unarmed. It seems risky enough by daylight.

If it is dark and I am certain my bear is dead, I will return to camp, trade hunting gear for tracking and field dressing equipment, including a strong, 6 or 12-volt flashlight and a double-mantel Coleman lantern, enlist the aid of one or two hunting partners for tracking and get my dragging crew ready.

Bear blood is especially easy to spot in the glow of a Coleman lantern, appearing almost fluorescent, making night tracking relatively easy. If the blood signs are not typical of a heart/lung shot bear, waning or light and steady, the trail notably long (more than 200 yards) and/or the bear has not laid down within 200 yards, rather than take the chance of stumbling upon a live, wounded bear while unarmed, break off the search and wait until first light in the morning.

With one of my partners silently following the blood trail, glowing lantern in hand, I like to keep to one side, using my flashlight beam to scan for black objects ahead.

Upon spotting a bear-like object on the ground ahead, a silent council is held, each of us giving whatever it is a thorough once-over with the light. If the bear is lying facing its back trail, it will be relatively easy to identify from a distance. In the beam of a flashlight, the eyes of a bear that has died a short time earlier will glow silvery (a dead bear's eye-lids remain open) and its tawny muzzle will be evident. Once satisfied the black, unmoving object is indeed a bear, and it seems dead, from a distance of at least 20 yards, I will sling a rock or dead branch just beyond it, watching for a reaction. Seeing none, I will then creep silently forward, alone, circling widely toward the bear's rear or backside.

Black bears almost always die lying on one side or the other. I would be suspicious of a bear lying square on its stomach with its paws and head extended forward; doubly suspicious if its eyelids were closed. At night, if things do not look "right," if it appears the bear might still be alive, I would retreat with caution and check the bear again an hour later.

When approaching a downed bear during daylight hours, legally armed, use no less caution. Keep your eyes on the bear, your weapon ready to fire. Move forward in the above prescribed manner, first watching for breathing motions and then checking for an eye reflex before touching the bear.

If a finishing shot is needed, aim for the bear's heart/lung region, not its head or neck.

Paul Fox, my Yukon hunting guide, always directed his hunters to take a finishing shot at a downed bear. "Shoot it in the neck whether it shows any signs of life or not," he would say, "just to be sure." Whether hunting dangerous grizzlies or relatively docile black bears, I am not so sure a neck shot is the ultimate finishing shot. If you can be sure of hitting a black bear's slender neck vertebrae (spinal bones), a neck shot will immediately anchor a bear for keeps. Having found spent bullets under fully-healed hides on the necks of at least two black bears and one grizzly, however, it is obvious to me that the spine is easy to miss in a broad-necked bear, especially when the hunter is excited, which is guaranteed.

Knowing a bona fide heart shot will stop a black bear within 10-20 seconds, I would go for the heart if I ever had a reason to take a finishing shot. However, I do not think it is necessary to shoot a black bear a second time unless there is reason to believe the bear is actually still alive. Unnecessary second shots have a habit of ruining choice cuts of meat and the hide.

Finishing a wounded black bear that is still alive, able to travel and in command of its sense is a considerable challenge. Unless winds are strong or moderate-to-heavy rain is falling, it can be very difficult to stalk near enough for a finishing shot, especially within the wet, dense, noisy and difficult-to-penetrate cover a wounded black bear will typically lead the hunter. Enormous stealth of two-men silently stalking is an essential prerequisite; also courage and reliable shooting instincts. When the bear is at last discovered, fueled by surging adrenaline, it will be a very fleeting target at best. If I was a trophy-hunting bow hunter caught in this situation, I guess I would forget about "Pope and Young" and start thinking "Boone and Crocket." For the bear's sake and mine, I would forsake my bow and load up a rifle for this job.

Particularly if the wounded black bear is large, this is the circumstance in which you should gird yourself for the possibility of danger. It is altogether likely a wounded black bear will do everything in its power to keep away from you, but never count on it. Always proceed as if you will soon have to fire at an approaching bear at very short range.

I guess if I were ever charged by a black bear, I would not worry much about ruining a trophy skull. I would aim at the center of the oncoming bear's nose or mouth. Between a black bear's eyes, the skull is thick and angled almost straight back. When hit by a hunter's bullet standing at ground level, a bullet might actually ricochet upward from a bear's skull, but it would certainly stun the bear, probably dropping it in its tracks. Hit in an eye, nose or mouth, a bullet would easily range back into the bear's brain, perhaps exploding the brain cavity but instantly dropping the bear. If I had a chance for a heart shot, I would take it, but upon meeting a feisty bruin head-on in close quarters, I would not mess around trying for a perfect shot. I would aim at any quick-kill target areas as best I could and would not quit firing until the bear was down for keeps.

Though probably a one-in-a-million event, an unstoppable charge by an enraged black bear is every bear hunter's worst nightmare. It is the underlying cause of poor shooting and the dread that contributes most to making black bear hunting the thrilling adventure it is. Though extremely unlikely, a few unfortunate hunters have experienced such a charge, and likely a few more will experience such charges in the future.

If you were to suddenly find yourself in this situation, unable to protect yourself, charged and mauled by a black bear, the recommended course of action is to immediately "play dead." Drop to the ground, curl into a fetal position, legs drawn up to protect your abdomen with hands and arms wrapped about your head and neck. If the bear thinks you are dead, it will soon become satisfied that it has accomplished what it set out to do, and it will then leave. Black bears do not eat humans, so don't worry about that. Regardless of any injuries you may suffer, do not move or make a sound unless absolutely necessary for at least 15 minutes after your attacker has departed. If near, your movements or sounds may trigger another attack. After 15 minutes have passed, attend to your wounds and then head for help or stay put until help arrives. When bear hunting, make it a standard procedure in your group that someone will head to your stand if you do not show up in camp within an hour after dark.

There is a better alternative, of course: shoot bears properly to begin with. Doing that, you will never have to make a finishing shot, you will never have to follow a live, wounded bear in a cedar swamp and you will never have to face a charging black bear.

Okay Dan'l, you can stop holding your breath. It is all over. Go ahead and cheer if you have a mind too. You deserve to be elated. You did everything right. You have accomplished something few hunters have accomplished. And like all bear hunters before you, not only did you harvest a much-revered black bear, but you obviously conquered something pretty tough to conquer inside. It is something to be especially proud of.

Boy, look at that bear. What a beauty, hey? Look at the size of that head. And those claws. Awesome. Is that fur ever thick and silky. Wow, he is heavy.

Hey, where is your camera?

Kill site photographs are the best. A picture of you standing by a bear hanging from garage rafters just does not do it. Photos of you, still somewhat dazed, and your bear, not yet field dressed, in the wilds where it lived carry an enormous impact. You will value such photos the rest of your life. In fact, succeeding generations of your family will consider such photos to be very precious. "Here is one of Great-Grandpa with the bear he got back in 2002," someone will say. "He was obviously a great hunter!"

Do it right. Dig out some paper toweling and wipe all visible blood from the bear. Tuck its tongue back into its mouth. Kneel beside it and hold the bear's head. Do not sit on the bear and do not position yourself five feet behind the bear to make it look larger than it really is. Do not make photos that lie. You will not fool anyone. Be proud, but do not make yourself look like a conquering hero. Handle the bear in a manner that reflects your respect for this once mighty creature. Do it right and you will forever be proud to show others your photos. Taken in good taste, others will also enjoy looking at your photos.

Good luck hunting,

Doc