Sam's Bear

By Dr. Ken Nordberg

[The following is the another of many older articles that will appear on my website. The original version of this account of my grizzly bear hunt in the Yukon Territory of Canada in 1982 appeared in Alaska Magazine in 1983. This version appeared in the Sept/Oct 2002 edition of Bear Hunting Magazine. It will become obvious, this is a story I love to tell. Please share what you learn from these articles with your hunting friends.]

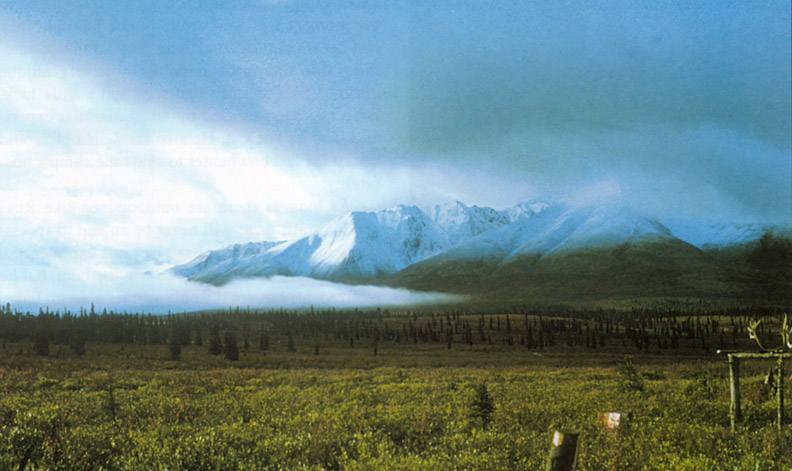

Freshly fallen snow above 5,000 feet on the surrounding mountains shortened the author's ram hunt, but allowed him to get a silver-tip grizzly on his final day of hunting.

Sam was a great fishing partner, ever eager to accompany me whenever I grabbed my rod and real and headed downstream to catch graylings in a deep pool a short distance from camp. When the fish were not hitting with their usual gusto, merely following my miniature black bucktail spinner into the shallows, Sam caught more graylings than I did. He would leap nimbly into the pond, grab them with his teeth and then, with little urging, drop them at my feet. His fishing technique was a bit unusual, but it was the best a Black Labrador Retriever could do.

Sam was also an actor. Some years earlier his right hind leg was clipped by the propeller of an outboard motor while he was retrieving a duck. Though no deformity was visible, Sam could spend an entire day running down and nearly snatching willow ptarmigan from the air as the cackled frantically a few inches ahead of his snapping jaws; the moment he smelled something good on a human's dinner plate or whenever he decided his ears needed some scratching, he limped so terribly that no one in camp could keep from giving him whatever he desired.

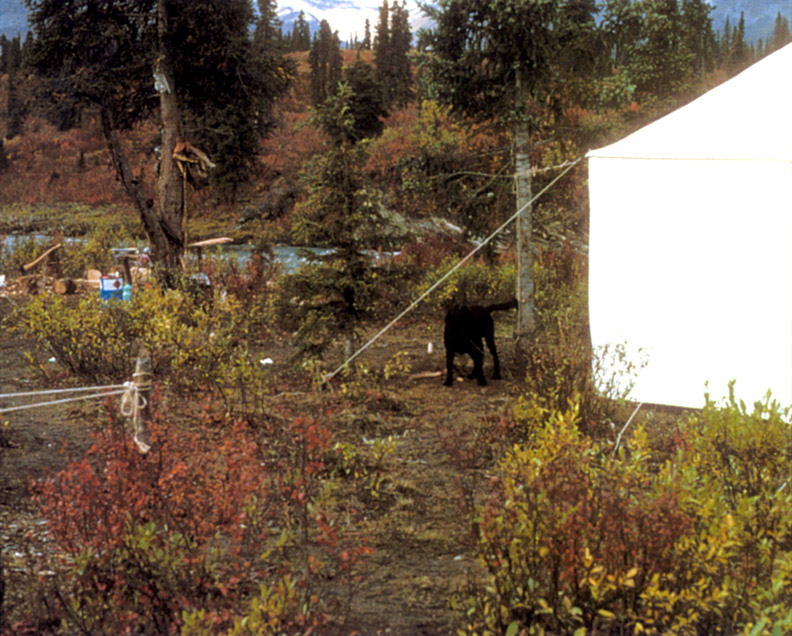

Black Labrador Retriever guard dog, Sam, attending to duties.

Sam's main duty in camp was to keep grizzlies from bothering our cook while my partner, Dr. Steve Fennell from Athens, Georgia, our two guides and I were away hunting. Our cook was a sister of our head guide, Paul Fox, a Tingit Indian from Ross River, Yukon who learned his trade under the guidance of Field Johnson, famous Shooting Editor, Jack O'Connor's favorite sheep hunting guide.

Steve and I, booked for a 21-day hunt, were only the third and fourth non-natives to hunt this region. Our main camp was situated near the headwaters of the the Stewart River (well known during the Yukon's gold rush) in the Selwyn Mountains of the Yukon Territory, within sight of the snow-capped McKenzie Range on the western edge of Canada's Northwest Territories.

While two hunters from Iowa that were there before us relaxed in camp and enjoyed a game of horseshoes the day before we flew into Misty Lake to replace them, a grizzly unexpectedly appeared near the pole racks draped with dried and smoked meat (moose, caribou and Dall sheep) and salted capes. Despite the commotion and excitement, one of the hunters managed to get his .30-06 from his tent and shoot the bear. Paul Fox began telling us all about it the moment we set foot in camp.

"The first shot didn't kill the bear," he said, shaking his head. "It took 16 shots and a half-a-day of tracking before we finally got it. We were luck. This bear just kept trying to get away. Most grizzlies are dangerous when wounded. If it had charged us in those heavy willows where we sometimes caught up to it, someone could have been hurt, maybe even killed."

"When you shoot at a grizzly, you want your first shot to kill the bear. If you only wound it, it will get mad and be made stronger, more dangerous and more difficult to kill."

With the stub of a pencil, Paul began to draw on a brown paper bag the outline of a bear standing up on its hind legs.

"Here's where I want you to aim when you shoot at a standing grizzly," he said, drawing an X on the middle of its chest. "Right here, you'll hit the bear's heart, make its lungs collapse and you'll also hit its spine, paralyzing the bear."

"In this brushy country, grizzlies can't see far when down on four legs. To see better they often stand up on their hind legs. When on a horse, always be ready for this. If a grizzly suddenly stands up nearby, your horse will go crazy. One hunter I had, a very good rider from Texas who broke horses for a living, was killed when his terrified horse ran under a tree branch. If your horse is frightened by a grizzly, get out of your saddle as quickly as possible. Ride with your toes loose in your stirrups and be sure to grab your rifle from your scabbard as you dismount."

"Here's where I want you to shoot when the bear is down on all fours and facing you," Paul went on, placing an X just under the chin of the bear's head on his second drawing. "Don't shoot at its head. Your bullet might ricochet back off its forehead. Only shoot its head if you have no other choice. If you hit a bear in its brain cavity, its skull might explode and then your bear won't qualify for the record book."

"If it's down on all fours and broadside," Paul continued, sketching the outline of another bear, "shoot it here." This time he put his X low and right behind the near shoulder of the bear.

"What about the so-called 'take-down shot' to a shoulder?" I asked.

"That's no good," Paul replied, grimacing. "A bear shot in the shoulder can run just as fast as a bear with four good legs, as fast as a horse. A shoulder shot will only make a grizzly mad."

"Remember what I told you," Paul admonished us, tapping his drawings with his pencil. "I don't want any more trouble with wounded grizzly bears."

"He sure didn't waste any time telling us how to shoot bears," Steve mentioned later.

"He fears grizzlies," I responded. "Probably rightfully so. His friend Field Johnson was killed by one."

It was an epic hunt. Before long Steve and I were peeling velvet from antlers of enormous bull moose and caribou. Late during our second week, Steve took aim at a near-record silver-tip grizzly as it devoured bones and other parts left behind at the site where I took my moose a few days earlier. Following Paul's instructions, Steve expertly dropped the bear with one shot.

On the second to the last day of our hunt, Paul and I spotted a long sought Dall ram with horns that would easily measure 40 inches around the curve. Up to this point we had glassed more than 100 sheep, only two of which were rams. Neither was large enough by Paul's standards, however. The trouble was, it was now almost dark, the 40-incher was lying at the top of a shale slide out of range and we were at the bottom, six miles from camp. "We'd better come back in the morning," Paul whispered.

That night I hardly slept. Outside the tent, the horses seemed restless too. About 1:00 a.m., one of them whinnied right outside our tent and later I awoke to the sounds of a horse walking past on the other side of the canvas next to my pillow.

Morning dawned gray and drizzly, and above 5,000 feet the mountains around us were covered with new-fallen snow. As I rounded a back corner of our tent to answer Nature's first call of the day, I looked down and gasped. There in the mud next to the canvas behind which I had slept were the fresh tracks of an enormous grizzly.

"Sam, c'mere!" I called. Then, "Paul, you have to see this!" Sam was first to appear. "Hey, dog," I said, "You're supposed to keep this from happening."

Sam briefly sniffed the tracks and then limped unconcerned toward the the cook tent to beg for something to eat.

"What's going on?" Paul soon inquired.

"Look at that, I answered, pointing.

"I sure don't like that," he said, glancing around camp. "That grizzly is too brave."

Later, as we finished eating our breakfast, Paul turned to his sister and said, "While we are gone, keep Sam tied up outside this tent and keep your rifle handy."

"It's right here," she murmured, motioning toward a rusty relic in the corner, a British .303 with a binder-twine sling. "It's loaded," she added.

At the 5,000 foot level of the shale slide where we had seen the big Dall ram the evening before, snow was six inches deep and falling so heavily that visibility was reduced to about 50 feet.

"That ram was near a cave," Paul whispered. "They sometimes go into caves in this kind of weather. It should be somewhere to our right. Let's take a look."

The cave was much larger than it appeared from below. The floor was about 15 feet in diameter, the ceiling was high enough to enable Paul and me to stand fully erect. Though currently devoid of sheep, it was obviously often used by them. The floor was covered with a thick and pungent layer of their droppings, some very fresh.

"All we can do is wait and hope it quits snowing soon," Paul said, "and this is the best place on the mountain to wait."

Three hours later, at noon, it was still snowing hard and showing no signs of letting up. At that point Paul suddenly turned to me and said, "I think we should go back to camp. I'm worried about that bear."

"Lead the way," I said, agreeing, now at peace with realization I would not take a ram on this hunt.

When we reached the river ford one mile west of camp, we could hear Sam barking excitedly. Then we heard the pounding hoofbeats of an approaching horse. Jiggs, my other saddle horse, was racing toward us wild-eyed and high-tailed, his mane rippling behind his neck.

"Jiggs is plenty scared," Paul noted. "I think we'd better hurry."

The moment we tied up the horses in front of the cook tent, Paul's sister rushed from the tent gasping. "That b-bear has been circling the tents all morning!" she cried.

Over the sounds of the wildly parking dog Paul asked, "Where is it now?"

"The last time I saw it" she stammered, "it was just across the river, about 30 yards away!"

My 7mm magnum loaded with 175-grain bullets (my intended bear rifle) was in my tent and I was about to race there to get it when Paul turned Sam loose. Sam immediately charged across the stream, apparently bent on teaching that grizzly that failing to heed the warning barks of a Black Lab guard dog was a serious breach of conduct. The moment Sam disappeared into the vermillion-leafed dwarf arctic birches and twisted spruces on the opposite bank, a rumbling growl was heard, sounding like distant thunder. Right then Sam reversed his course and raced headlong back toward camp. The trouble was, there was an enraged silvertip grizzly on his heels.

At this point I noted I was the only person holding a firearm. Not only that, I noted I was holding a mere .270 loaded with 130-grain bullets, wonderful cartridges for sheep but likely horribly deficient for enraged grizzlies. I held my ground nonetheless, and my breath, I then unsnapped the leather bullet case on my belt. "This is going to be a war," I was thinking.

While Sam scampered across the river with his tail curled tightly between his hind legs, the grizzly suddenly halted and stood up. From where I stood, it appeared to be ten feet tall. "This must be how David felt when standing before Goliath," I fleetingly thought as my rifle came to my shoulder. Then Paul's drawing on the brown paper bag came to mind and the crosshairs of my scope settled on the spot where the X was drawn. At the shot, the towering bruin dropped to the ground like a sack of potatoes.

"Is it moving?" Paul asked.

"Nope," I answered, staring at what I could see of the bear through my now wavering scope.

"Can you see its neck?" Paul inquired.

"Yes, I think so," I croaked.

"Shoot it again in the neck, just to be sure," he said.

"Okay," I murmured, and shot. I was later humbled when we discovered this second shot had missed the bear completely.

The awesome business end of the author's near-record silvertip grizzly taken in the Yukon Territory.

It took 30 minutes and two cups of coffee to return to normal, about the right amount of time to wait before approaching a downed grizzly presumed dead. Because none of the horses could be coaxed to cross the river, Paul and I crossed the cold river on our own, me with my 7mm Magnum in hand and Paul with a skinning knife, a sharpening stone and an empty oat bag for the bear hide.

Dr Ken Nordberg getting his first close look at his silvertip grizzly.

After the unmoving bear's right eyed failed to blink when touched with the tip of a long stick, proving the bear was indeed dead and safe to handle, Sam splashed across the river, rushed up to the grizzly, grabbed its right ear and, while growling, shook its head vigorously. After that, he had other important matters to attend to, catching some ptarmigans just west of camp, for example.

Good Luck Hunting,

Doc